The Bentley that finished Le Mans – with a single driver

In its 100 year history only British driver Edward Hall has ever completed the Le Mans 24 Hours single-handed, in this special Bentley prepared by Rolls-Royce. Andrew Frankel travels to Georgia in the US to find a car that is still able to go the distance

Andi Hedrick

Most of us are aware of what is regarded as the greatest ever feat of endurance at Le Mans. It was Pierre Levegh’s attempt to do the entire race alone, sure he could hear something awry in the engine of his Lago-Talbot and convinced that he alone had the mechanical sympathy to make it last the distance. In the end, the irony was that it wasn’t the engine that failed, but the driver trying to look after it when, at or beyond the point of clinical exhaustion while leading by miles with little more than an hour to go, he missed a gear and blew said motor to bits. Of course the race win was duly seized by Mercedes-Benz, and brought Levegh to the attention of Alfred Neubauer who hired him for Benz’s next Le Mans outing in 1955 with the catastrophic consequences we all know so well.

Those are Bentley lines but Rolls-Royce modified the car for Eddie Hall, who was uncatchable in the Ards TT

Fewer, I think, know of Luigi Chinetti’s successful attempt to win the race in a Ferrari in 1949, driving for over 22½ hours because the car’s owner, entrant and co-driver Lord Selsdon was so ill he could only manage just over an hour in the car on Sunday morning. Chinetti’s win was his third, 17 years after his first (a span to this date equalled by Hurley Haywood alone) and at the age of almost 48.

And how many now recall his first win in 1932 when it was Chinetti whose health failed, leaving Raymond Sommer – whose entire Le Mans experience to date added up to 15 laps the year before – to drive alone to victory for 21 hours? Not many, I’ll warrant.

In 1950 Eddie Hall once again tackled Le Mans in his by now long-in-the-tooth Bentley, finishing eighth

LAT Photographic

But more, I am confident, than the number who can name the only driver reputed to have completed the entire race by himself. His name was Edward Ramsden Hall and his story and that of his Bentley counts among the greatest lesser known Le Mans tales of all. I hope I can do it justice, not least because I’ve just returned from the Blue Ridge Mountains of northern Georgia where I’ve been driving that very car.

First, a small hygiene notice. I chose the word ‘reputed’ in the previous paragraph with care. For myself there is no doubt that he did as suggested. Despite quite a lot of searching I have not found a single credible authority to say he did not. Doug Nye is sure, which is good enough for me, and cites The Autocar’s race report which states that “Eddie Hall brought the Bentley home in eighth place single-handed”. Additionally the massively reputable Revs Institute which owns the car today says not only that Hall drove the race alone, but also that his co-driver had to be consoled by Hall’s wife Joan when it became clear he was not to be driving at all that weekend. Perhaps as compelling is the “Green overalls!” remark Hall made when asked by our very own DSJ how he coped with 24 unrelieved hours behind the wheel.

“It was, and remains, the only Bentley ever prepared for racing by the Rolls-Royce factory”

So can I state without equivocation that he did the race solo? I think so. Which leaves the only remaining area of doubt being whether he was the only person ever to do so. I’ve not heard of anyone else, but can I say as fact that there was no little fancied runner in the mid-1930s who quietly toddled round all by himself for a day and night? I cannot, but I doubt it. If you know of any such person, I’d be grateful for the enlightenment.

But back to Edward Hall, whom we, like everyone else, shall hereafter be referring to as Eddie. He was a remarkable man whose fortune from the family textile business in Yorkshire allowed him considerable freedom to pursue his passion for racing. Born in 1900, his competition activities were restricted to hillclimbing until 1928 when he took part in the first Tourist Trophy race to be held at the Ards circuit in County Down; this was also the year he competed in the Winter Olympics in St Moritz for the British bobsleigh team. He’d continue to race at Ards each year until the TT left for good after the 1936 race when eight spectators lost their lives as a car spun into the crowd.

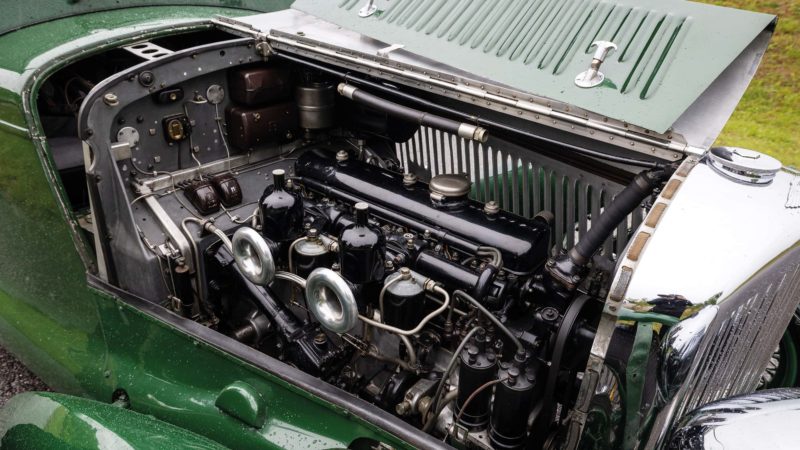

Rolls installed a 4½-litre engine in the Bentley in 1936.

Andi Hedrick

In his early outings he drove a Lagonda, an Arrol-Aster, a Bentley and two MGs, coming second in class twice. But our story picks up in 1934 when, enthused by Rolls-Royce’s take on what a modern Bentley should be, he swiftly ordered a new ‘Silent Sports Car’. This was chassis B35AE, and you’re looking at it.

But Eddie had no intention of racing his new car. Rolls-Royce did not build racing cars even with Bentley badges, but what we’d recognise today as grand touring machines. His plan instead was to use it to reconnoitre the Mille Miglia route in which he planned to compete in one of Earl Howe’s MGs. Leaving nothing to chance, he did two flat-out laps of the 1000-mile route with Joan as co-driver, marvelling at the speed and reliability of his new acquisition. The same sadly could not be said of the MG which retired, but not before making Joan the first woman to enter the race.

Now convinced the Bentley could do well in the TT he approached Rolls-Royce for support only to be told by technical director WA Robotham that very idea was “sheer lunacy”. But Eddie was nothing if not persuasive and the factory consented to gently warming its 3669cc engine and sending along a chief mechanic. More important was the commissioning of a new lightweight streamlined body with a long-range fuel tank, transforming the car’s speed and range. And but for the handicapping system which gave slower cars more time to complete the course, he’d have won, smashing the class course record and finishing just 11sec behind the ‘winning’ MG, which had been given a 1min 20sec advantage. He was back in 1935, proving once more the fastest car in the race, and relegated to second on handicapping alone.

“For 1936, Eddie commissioned Barkers to make another racing body – the one you see today”

So for 1936, Eddie went all out, commissioning Barkers to make another racing body – the one you see on the car today complete – with a 48-gallon tank in the back allowing him to complete the race in full without refuelling. He also bought an entire other Bentley in order to nick its larger 4257cc engine which Rolls-Royce tuned to the limit of what was allowable under the regulations.

Next, he entered it for Le Mans in what turned out to be the only year outside World War II that the race was cancelled. But at Ards the story was the same – fastest on the road, second at the flag, confounded by the handicappers to the last.

But by then the Bentley was already acquiring claims to fame: it was (and remains) the only Bentley ever prepared for racing by the Rolls-Royce factory; it was (and remains) the only car to have been the fastest in three consecutive TTs and its average speed for the final race – 80.81mph – set a record that will stand for all time.

A damp day for open-top driving in Georgia

Andi Hedrick

The car would not race again until 1950 when Eddie, now living in Canada, decided to have one more crack at Le Mans with the 16-year-old car, which I think makes it the oldest car ever to complete the race. He had an ugly hardtop built to sit on the pre-war body and an aerodynamic cowling to sit over the front radiator, all to help its speed down to Mulsanne. Aston Martin racer Tom Clarke was chosen as his co-driver but, as the Revs Institute points out, “he [Eddie] hated sharing his drives with anybody else”.

And we know what happened next: a month off his 50th birthday, Eddie chuntered around in his green overalls, an increasingly disconsolate Clarke in the pits, bringing the Bentley home despite half an hour lost to tyre trouble, at an average speed of almost 83mph to place eighth out of 29 finishers and 60 starters.

Eddie had one more crack at the race in a Ferrari the following year but retired at half-distance. For the old Bentley however, its race career was over. Eddie sold the car to Briggs Cunningham and it was then passed to the Collier Collection when Miles Collier bought the bulk of the Cunningham cars. Renamed the Revs Institute, it remains in its care to this day.

Which is a rainy, murky day in Georgia where the car has been brought from its Florida home because the roads are better. Lacking its hard top – Eddie is believed to have left it in France – and radiator cowling, it looks very different to how it raced at Le Mans. But it’s not: those details aside and save the fitting of Lucas headlamps, it is essentially as it was when it crossed the finish line at Le Mans in 1950. And despite the weather, it is running perfectly.

Nor does anyone remind me of my responsibility to look after the car. On the contrary every encouragement is given to get out there and really drive it, despite the weather and Dunlop racing rubber entirely unsuited for the conditions.

Eddie is reputed to have been a tall man, but perhaps only by the standards of the day, for there’s no way he’d have been able to drive for so long if he were my height. I’m 6ft 3in and could only drive the Bentley wearing thin-soled, narrow race boots with my knees either side of the wheel.

No matter. While you sit in a slender duralumin bucket, elbows over the cut down sides, other than its total lack of trim the cockpit itself – its steering wheel, dials and switchgear – are no different to any other ‘Derby’ Bentley of the era. Switch on the ignition, pull the advance-retard lever all the way back, thumb the starter and Eddie’s Bentley woofles to life. Its exhausts are near unsilenced but while its voice is deeper and louder than any standard Rolls-Bentley, it still manages to sound urbane, a million miles from the ‘bloody thump’ of similarly sized engines made by Bentley itself in the 1920s.

“It’s the handling I’ll remember longest, for the Bentley just feels so very well sorted”

I’ve driven a Rolls-built Bentley of this era, knowledge I’d rather not have right now, because it’s causing me to make mistakes. There is no syncromesh on first and second gears, but the change is usually still simplicity itself. Except my first attempt only finds the gear after a graunch of protest from the box, after which the engine revs fall hardly at all. Nowhere in all I’ve read about this car are race ratios mentioned, but they’re all in there. First is high enough to be used as a proper gear, second is super short, third feels about right while fourth is long – long enough to pull perhaps 120mph on the run down to Mulsanne.

The motor is peakier than I’d expected too, at least until I remembered Rolls-Royce had raised the compression to a heady 9:1 to coax 163bhp from the motor, up from a road standard 125bhp. But when the moment comes, the old Bentley fairly surges up the road, aided by superb mid-range torque and an all up weight of just 1375kg, a veritable sylph by Bentley standards.

But it’s the handling I’ll remember longest, for the Bentley just feels so very well sorted, planted absolutely, resolutely four square on the soaking asphalt. Short of fitting slicks the rubber could scarcely be less suited to the conditions but it didn’t seem to matter: the car is so accurate and reassuring I just went faster and faster until I reached the speed I’d not exceed in a modern car on these wet roads. And it didn’t budge at either end, not even once. I’ll remember too, the pedals. The last time I drove a car better set up for heel and toeing it was a racing 1965 Alfa Romeo GTA.

I could see, many decades and thousands of miles away from Le Mans and Ards, what drew Eddie Hall to this car. It makes me wonder what a proper works effort by Rolls-Royce could have achieved in France in the 1930s. Instead I’ll just reflect instead on what we have here: the only car to win on merit three TTs in a row, driven by the only driver to win three TTs on merit in a row in the same car. The only Bentley ever prepared for racing by Rolls-Royce and the only car, so far as I know, to have been successfully driven solo at Le Mans. Yet most people who ask where I’ve been and what I’ve been driving, even proper enthusiasts, have never heard of the car, let alone its indefatigable owner. I hope these words go some little way to bringing both to the wider audience they richly deserve.

Hall’s Bentley is now among the 112 cars of the Revs Institute collection – and it’s a joy to drive even in the rain

Andi Hedrick